Reviews 2017

✭✭✭✩✩

music, lyrics, book and directed by by John Christenson

• Catalyst Theatre, Grand Theatre, London

February 7-11, 2017;

• Persephone Theatre, Saskatoon, SK

March 1-15, 2017

• National Arts Centre, Ottawa

March 29-April 15, 2017

Johannah: “Family always comes first”

Edmonton’s Catalyst Theatre has launched its tour of its rock musical Vigilante at the Grand Theatre, London. John Christensons’ 2015 musical, nominally about the infamous Donnelly family, begins its run three days after the 137th anniversary of the Donnelly Massacre of February 4, 1880, in Lucan, Ontario, only 30 kilometres from London. What Ontarians will find rather odd about Christenson’s musical is how free he is with the facts of the story. What Ontarians view as history and which has been treated as history by local playwrights, the Albertan composer regards merely as material that can be fictionalized to suit his purposes. While Vigilante is well designed and well performed, it is an unpleasant feeling to see local history so cavalierly misrepresented.

Christenson begins the story of the Donnellys in County Tipperary, Ireland. The Catholic community is split between a secret society called the Whiteboys, who advocate the killing of all Protestants and the burning of their houses, and Catholics who opposed their violence and were called Blackfeet. The Whiteboys prejudice against Blackfeet is almost as virulent as their prejudice against Protestants.

As history goes, so far so good, but Christenson soon needlessly diverges from history. He gives James and Johannah only six sons – Will (Carson Nattrass), Daniel (Kris Joseph), Robert (Erin Morin), Tommy (Scott Walters), Johnny (Lucas Meeuse) and Michael (Benjamin Wardle), who is repeatedly called the youngest. In reality their children in order of birth were James Jr., William, John, Patrick, Michael, Robert, Thomas and Jenny. Thus, the birth order in the musical is confused, children Patrick and Jenny are omitted and a non-existent son Daniel is added.

Christenson shows that tensions between the Donnellys and the community rise until James is framed for killing Patrick Farrell and goes into hiding. At James’s trial the only eye-witness has gone missing and James, despite Johannah’s pleas is hanged for the murder. In reality the story in more interesting since, in fact, Johannah’s pleas along with others’ had the effect of reducing James’s sentence from hanging to penal servitude for seven years. After his term is over James returns home. His return may have led to the idea of the massacre in the first place.

The Donnellys are accused of burning down a barn and killing six horses but all claim to be at the bedside of Daniel, who was dying of tuberculosis. (It was James Jr. died of an illness leading one to think Christenson invented “Daniel” to avoid confusion with James Sr.) The constable comes to arrest Johannah for the deed, enraging the family who drive him away. Out of grief, Johannah swerves from her usual call for restraint and calls for vengeance. All the fierce-looking but peaceable brothers know this is “only the grief talking”, but Michael ruins the family’s so far spotless reputation by stabbing the youth who accused Johannah.

This event is what in Christenson’s version leads to the massacre. Ciaran Connelly, the James Donnelly’s antagonist in Ireland, has moved to Biddulph also and organizes the massacre. Not only is Johannah killed but all five of her remaining sons.

Anyone with a brief acquaintance of the story will know that this is simply not true. in his Director’s Note, Christenson says, “While it is tempting to want to establish exactly what happened to the historical Donnellys, I wonder if it’s ever really possible, in the end, to know the full truth of anyone’s story?... One thing that seems certain is that we’ll likely never know exactly what the Donnellys did, or what was done to them, or why it happened, or what they were like as people.”

In reality, one of the things we do definitely know about the Donnellys is who died in the massacre – and it was not the entire lan as Christenson so gruesomely depicts. Rather the five killed were James Sr., Johannah, John, Thomas and Bridget, James Sr.’s niece, thus leaving William, Patrick and Robert alive. Michael, who Christenson shows killed in the massacre, died a year earlier in a pub fight.

The question is,”What does Christenson gain by misrepresenting the known facts of the story?” What he gains is the ability to whitewash the Donnellys completely, except for Michael’s actions, and to condemn the survival of Old World vigilantism in the New World. Christenson’s existential excuse that no one can know the full truth about anyone has allowed him to turn an extremely complex story into an extremely simplistic one. The Donnellys are good and the Whiteboys are bad.

Anyone who really knows the history of the Donnellys will know that the story is much more ambiguous and, indeed, it is this very ambiguity that has attracted so many writers to it for so many years. A signal example is James Reaney’s trilogy The Donnellys – Sticks and Stones (1975), The St. Nicholas Hotel (1976) and Handcuffs (1977) – one of the high points of 20th century English Canadian drama. Just last year the Blyth Festival presented The Last Donnelly Standing by Paul Thompson and Gil Garratt about Robert Donnelly, who emphatically was not killed in the massacre. The play demonstrated that a dramatic work with songs can be created by adherence to known facts and by highlighting ambiguities just as well as by ignoring them and to far greater effect.

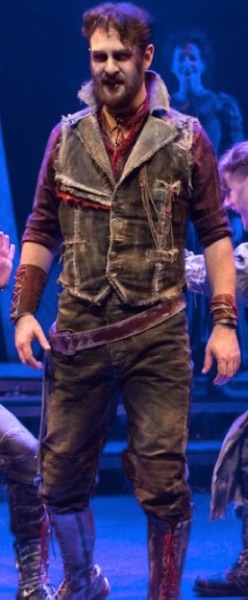

Given the major flaw in Christenson’s justification for creating his fictional Donnellys, the productions itself is well imagined. The five-piece rock band is on stage throughout to underline the show’s non-realistic presentation of events. James Robert Boudreau has created a set of several ramps and vertical pieces that under Beth Kates’s lighting could be construed as either a barn or a house. Christenson’s concept is that we are seeing the ghosts of the Donnellys and Narda McCarroll’s costume and makeup design is perhaps the most striking feature of the show. While the men’s silhouettes suggest 19th-century clothing, they wear modern punk-style combat boots, black jeans and varying punk haircuts with white makeup and red-rimmed eyes. Only Johannah’s torn red dress reflects period style.

The cast is very strong. Jan Alexandra Smith has the widest dramatic arc from falling in love to calling for revenge and she has a strong voice and the unfailing dramatic intensity to dominate the stage at her every appearance. As James, David Leyshon, whom most would associate with comedy, proves equally at home in tragedy and is an equally forceful presence. He also has a lovely tenor voice that serves him well in the scenes where James comforts Johanna that things will turn out well.

As Will, Carson Nattrass serves as the narrator for the show and delivers most of the story with a snarl. Kris Joseph plays the fictional”Daniel” but is especially strong as the fictional Ciaran Carroll who taunts the Donnellys in Ireland and Upper Canada in a high, seemingly unconcerned voice carrying a nasty undertone of menace. Eric Morin has a particularly fine voice and it is too bad his character Robert has only one solo number. As Johnny and Michael, Lucas Meeuse and Benjamin Wardle suitably act younger, and Wardle more withdrawn, than the other brothers.

Christenson’s music ranges from Irish folksong to rock anthems and ballads, but the overwhelming and frankly tiring tone is of anger reinforced with strong rhythmic beats of the drum. Choreographer Laura Krewski concentrates on having the performers act out with arm gestures the subject of the songs as in fighting or clearing land. She has the group indulge briefly in a little Irish folk dancing, but she unimaginatively keeps falling back on having the group form a phalanx with Ma Donnelley at the head stomping with one foot while they sing.

Christenson ends the show with the ghosts of the Donnellys calling for vengeance but since he has left none of them alive it is unclear who is supposed to avenge them. If, as he claims, Christenson wrote the musical out of worry for the rise of vigilantism in North America, it is hard to see how calling for vengeance in any way helps his cause.

In opening the show in London, Christenson probably couldn’t have known that the Lucan Area Heritage and Donnelly Museum would set up a booth with a large family tree of the Donnellys detailing exactly who did and did not die in the massacre. Patrons could therefore very easily crowd around the display at intermission and after the show to wonder why the known facts of the event were so different from what Christenson presented. Christenson may have wanted to condemn vigilantism in 2015 when the work premiered, but in 2017 in a world of “alternative facts”, an Albertan’s artistic licence with Ontarian history simply does not sit very well. We can appreciate the skill of the performers, but we know that turning the story of the Donnellys into a simple tale of good versus evil does no justice to the story or the complexities of real life.

©Christopher Hoile

Note: This review is a Stage Door exclusive.

Photos: (from top) Scott Walters, Eric Morin, Lucas Meeuse, Jan Alexandra Smith, Kris Joseph, Carson Nattrass and Benjamin Wardle. David Leyson; Erin Morin, Carson Nattrass, Benjamin Wardle, David Leyshon and Lucas Meeuse; Benjamin Wardle, Lucas Meeuse, Carson Nattrass and Eric Morin. ©2017 David Cooper.

For tickets, visit www.grandtheatre.com, www.persephonetheatre.org or https://nac-cna.ca.

2017-02-12

Vigilante